Workshop 6: Creativity

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

“Change is not required because survival is not mandatory.” Peter Drucker.

The final session of the CEO workshop series drew on some of the best ideas that had gone before and directly addressed the theme of this year’s World Economic Forum: the creative imperative.

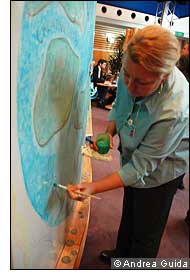

Throughout the series, the team from MG Taylor Value Web that had co-designed the workshops had been gathering up the best ideas, quotes and photographs on “hyper tiles” and pasting them on to mobile magnetic walls. A talented scribe, Alicia Bramlett, had also illustrated the main themes to have emerged from the sessions in a series of real-time cartoons. The workshops had collectively amassed a treasure chest of intellectual capital that it was now time to spend.

Geoffrey Moore, the venture capitalist and author of Dealing with Darwin, a book on corporate innovation, opened the workshop with some provocative banter. For years, he suggested, US companies had been playing on their home field. They had benefited from the biggest domestic market in the world, a great education system, and dynamic capital markets. “We held the World Series and we never invited other countries,” he said.

But the world was changing fast. Home advantage had now crossed across the Pacific to China and India. US companies had downsized and outsourced to stay in the game but they now needed to create new value propositions and strategic advantages to flourish longer term. How could they innovate to survive? Thinking outside the box was the name of the game. “And when you think outside the box at Davos there are some pretty cool people to do it with,” said Mr Moore.

The object of the exercise was for self-forming teams of three to go round the room collecting intellectual “seashells” from all the material pasted on the walls. The teams had to choose three ideas that appealed to them and which they believed would become the new best practices of tomorrow. Inspired by these ideas, they had to create an imaginary company and pitch it to potential investors. Truth be told, all the ideas were hyper ventilated. But the freewheeling discussion that followed raised some thought provoking questions about how to nurture a culture of creativity.

All participants agreed that companies needed actively to encourage employees to come forward with as many fresh ideas as possible but that they had to kill the bad ones quickly to focus resources on the most promising. “We took on too many projects and never invested in any one sufficiently enough to ensure that they succeeded,” said one industrialist. “We said that one of our strengths was focus. But we focused on everything.”

Another executive cited the example of a US pharmaceuticals company that employed a director specifically to drown the bad ideas quickly and ensure that resources were thrown at the most likely drugs. “If you get rid of the bad ideas early then there is no concept of failure. It also helps create a culture of courage and the alignment of interests.”

But how can companies “celebrate” these failures so as to encourage disappointed employees to keep coming up with fresh thinking? Give them a cake? One suggestion was the CEO had to show that they were interested in the ideas and had investigated them with respect, humility and curiosity. The best way to deal with disappointed innovators was to pay them due attention rather than brushing them aside.

Some participants admitted that their companies were so highly structured that they tended to suppress creativity. “We are stuck in these hierarchical organisations which are pretty poor at innovation,” said one. However, another businessman argued that it was senseless for companies to seek out creative CEOs. The chances of recruiting a Steve Jobs or a Bill Gates were minimal. What was needed was a chief executive who would actively encourage ideas to bubble to the surface and create an excellent process for winnowing out the best ideas.

Mr Moore said it would be a mistake to believe that innovation ended when the new ideas had been harvested. It was just as important to deploy these new ideas in real life and to optimise their entry into the market. This counted as innovation too. “The more disruptive or innovative your idea the more it is likely to disrupt the other parts of your business be it management or marketing. Hierarchical companies are pretty good at doing the deploying and the optimising.”

What struck one of the chief executives about the discussion was the enthusiasm of the participants and the total absence of cynicism. Perhaps it was something in the mountain air, or the nature of this self-selecting group, but it was never like this in real life, he said. The lesson that he would be taking back from the session was that “there are no stupid ideas”. An interesting thought to come out of a group of people who like to think they are among the smartest on the planet.

Comments